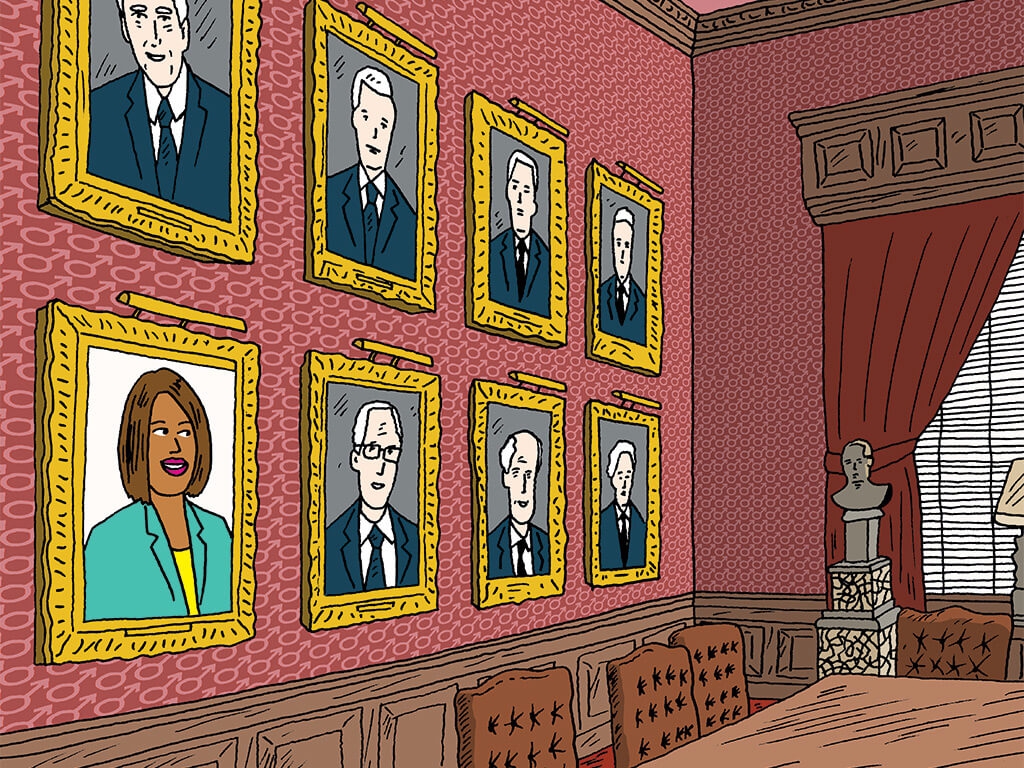

When Zabeen Hirji joined the Royal Bank of Canada as a teller in 1977, all of the company’s executives were white men. By 2015, eight years into her tenure as the bank’s chief human resources officer, women held two-fifths of those roles at RBC and visible minorities, 16%.

(Illustration by Peter Arkle)

RBC’s leadership may not yet represent the diversity of the population at large, but it’s far ahead of the broader business world. Too many companies of all sizes are stuck closer to the “before” in that tale of transformation than the “after.” They often blame the so-called “pipeline problem”: the notion that there aren’t enough qualified women or people of colour available. The more likely culprit is unconscious bias, a set of assumptions that cause recruiters or managers to overlook candidates because they don’t fit their mental model of the ideal employee. One solution? Mandate that every slate of candidates must include people from under-represented backgrounds.

Plenty of firms pay lip service to the benefits of organizational diversity, bringing in consultants to run marathon training sessions. But the upper ranks of the business world remain disproportionately male and monochrome. In a study recently published in Harvard Business Review, researchers analyzed three decades of data from 829 U.S. firms and found that compulsory diversity training actually reduced managerial diversity.

Done right, diverse slate hiring policies—which require at least one woman or person of colour to be among the candidates considered for a job—remove the easy excuses that cheat the under-represented out of a shot at key roles. For example, a hiring manager might assume a qualified woman with young kids wouldn’t want a role requiring a lot of travel. By including her in the candidate pool, the woman gets to make that call—not someone making assumptions.

Many large organizations have embraced such regulations, including the NFL (where “The Rooney Rule,” is named for early proponent and Pittsburgh Steelers owner Dan Rooney), Pinterest, Facebook and RBC, the latter of which has a goal of granting half of new executive appointments to women and one in five to members of visible minority groups. To help achieve that target, the pool of potential hires at that level (and, for that matter, the two below it) must contain at least one diverse candidate. Recruiters who fail to meet those thresholds are sent back to look harder. Since the bank’s workforce is quite diverse at the lower end of the org chart, it does a lot of promoting from within. Any internal candidate who goes up for, but does not get, a new role is assessed and given a development plan to increase his or her chances next time. “You’ve got to develop people early in their careers to fill that pipeline,” says Hirji.

It’s equally important to avoid tokenism—something organizations can succumb to with diverse slate policies, says Dnika J. Travis, who leads the Catalyst Research Center for Corporate Practice: “An organization can say, ‘We’ve accomplished something because we have one [diverse candidate].’” She cites research from the University of Colorado Boulder, which found the likelihood of hiring a diverse candidate increased greatly when more than one was in the running. Why? Because it forces employers to evaluate each prospect on his or her own merits—not as a representative of a group.

Executives might dismiss diverse slate policies as political correctness run amok or as an affront to meritocracy. That’s wrong, says Hirji: “Our clients are diverse. We need people [who] understand their unique needs so we can better serve our clients and grow our business.”

Murad Hemmadi,”Improving Diversity in upper management means changing frontline hiring.” (October 24, 2016)

https://www.canadianbusiness.com/innovation/diverse-slate-hiring/